A Brief Bio

Sophie

Blackall was born in Australia in 1970. She learned how to draw on Australian

beaches with sticks. She has a Bachelor’s in Design and has had many galleries

of her work in both Sydney and Melbourne. But in 2000, she was drawn to New

York, where she has remained ever since. Her work has appeared in several

newspapers such as the New York Times, the Boston Globe, and the Wall Street

Journal. Since coming to New York, she has illustrated over 30 children’s

books. Her children’s books include: 2015 Caldecott Medal Winner Finding Winnie, Ezra Jack Keats

Award-winning Ruby’s Wish, and A Fine Dessert, which has since garnered

much controversy.

Sophie Blackall Exhibition Video

Winning

the Caldecott

An Annotated Bibliography

Mattick,

Lindsay. Finding Winnie: The True Story of the World’s Most Famous Bear. Illustrated

by Sophie Blackall. Little Brown and Company. 2015. 56 pages. Ages 3-6.

It’s

bedtime and just like any young child, Cole wants to hear a story. Cole’s mama

begins her tale – a true story about a veterinarian named Harry who is headed

to Europe to fight in World War I. Along his way, he stumbles upon a black bear

cub at the train station and thinks, “There’s something special about that

bear.” So begins Harry’s adventures with Winnie, who soon becomes the army’s

mascot and has a job of her own. Sophie Blackall’s illustrations bring Winnie

and her story to life, often making the reader laugh. She portrays the setting

perfectly right down to the buttons on the uniforms and the ships the soldiers

take across the ocean. When the army is to be shipped off to France, Harry has

to decide how to keep Winnie safe. Lindsay Mattick paints images with her

words: “The trained rolled right through dinner and over the sunset and around

ten o’clock and into a nap and out the next day,” effortlessly tugging the

reader along word for word. The bedtime story format not only blends the two

separate stories together, but also allows time for young listeners to ask

questions of their own, just as Little Cole does. The London Zoo is where

Christopher Robin first meets Winnie, and he too knows, “there’s something

special about that bear.” The young boy names his teddy bear after the real

Winnie and the rest is history. An album at the end of the story shows actual

photographs of Harry and Winnie that will awe fans of Winnie the Pooh or anyone

who loves animals. There has been no better telling of the true story of how

Winnie the Pooh came to be.

Jenkins, Emily. A

Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat. Illustrated

by Sophie Blackall. Schwartz & Wade Books. 2015. 44 pages.

Many

of us may recognize Sophie Blackall’s art instantly when we look at A Fine

Dessert. Her work has been in popular children’s books like Ivy and Bean

and this year’s Caldecott Award Winner, Finding WInnie. If you are

familiar with her art, you know that she does extensive research before

illustrating a book. The book tells the story of a dessert through the

centuries. For example, the first story takes place three hundred years ago and

begins with a woman and her daughter picking blackberries. The woman milks the

cow and then beats it into whipped cream. The girl prepares the berries with

water from the well and mixes it with the cream. They leave it to chill in an

ice pit in a hillside and later serve it for supper. The second story is more

troubling. It begins two hundred years ago and features two slaves, a girl and

her mother, picking berries and preparing the dessert for their masters. The

first picture shows the girl and her mother smiling at each other as they pick

berries. Another picture shows the girl beating the cream - the first image she

is smiling, the second she is frowning because her arm aches and in the third

she has a big grin. A couple pages later, the girl and her mother serve their

masters the fine dessert. The last image in this story is the most disturbing

as are the words - “later, the girl and her mother hid in the closet and licked

the bowl clean together,” (Jenkins, p. 16). The next story takes place only one

hundred years ago and features a white girl and her mother making the same

dessert in more modern times. Again, the women are doing all of the work. The

last story has a very different tone. It takes place only a couple of years ago

and features a father and his son making the dessert. The last image in this

sequence shows a gathering of friends and family of different racial

backgrounds and ages, all enjoying this fine dessert.

Though the last story and

picture is uplifting, we can’t ignore the second story. While we understand the

author did not want to skip over this period in our history, we feel that the

story grossly oversimplified slavery. There is no mention of slaves or slavery

besides the word “master.” Imagine a child confronting slavery for the first

time in this book. The story makes it seem like it wasn’t a big deal.

Furthermore, we were uncomfortable with all of the smiling between the mother

and girl while they were preparing food for their master. While slaves may have

tried to find joy in parts of their work, including these smiles here with no

context is inappropriate. The last image in this sequence is mind-boggling. It

shows the slave girl and her mother hiding in a closet licking the bowl after

they served the dessert they worked incredibly hard to make to their masters,

again with no context. How is a child supposed to interpret this image? A

picture book is no context for the topic of slavery and the way the author and

illustrator tried to handle the topic is a perfect example of white privilege.

Although the author and illustrator did their research and had the best of intentions

(as gathered from their notes at the end of the book), the topic was completely

oversimplified.

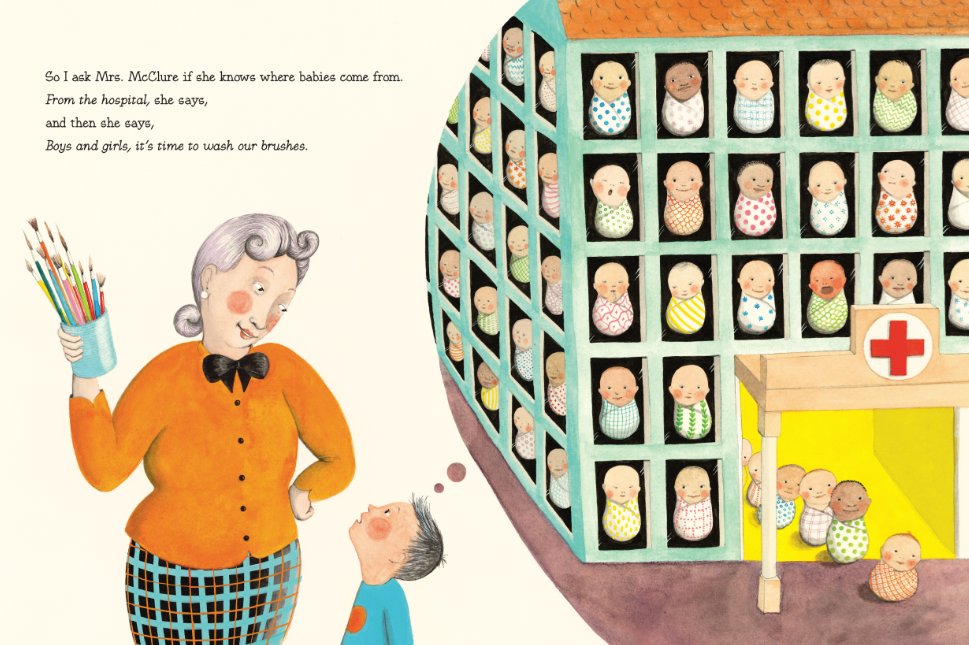

Blackall, Sophie. The Baby Tree. Illustrated by Sophie Blackall. Nancy Paulsen Books. 2014. 40 pages. Ages 5-9.

Blackall, Sophie. The Baby Tree. Illustrated by Sophie Blackall. Nancy Paulsen Books. 2014. 40 pages. Ages 5-9.

This

adorable picture book deals with the dreaded question, “Where do babies come

from?” in an engaging and appropriate way. After breakfast, Mom and Dad tell

their son that a new baby is coming. This brings up a lot of questions for the

boy, especially where babies come from. The boy sets about asking his

babysitter, his teacher, and his grandfather this question, all of whom give

him different answers. This confuses the boy, until he asks his parents. They

answer his question in a satisfying and age appropriate way. Blackall’s words

and illustrations capture a realistic depiction of a child’s curiosity and his

conversations with adults. Done ink and watercolor, the images bring alive the

mental images one gets from the words.

Rosoff, Meg. Meet Wild Boars. Illustrated by Sophie Blackall. Henry Holt and Company. 2005. 40 pages. Ages 3-8.

Rosoff, Meg. Meet Wild Boars. Illustrated by Sophie Blackall. Henry Holt and Company. 2005. 40 pages. Ages 3-8.

Meet

Wild Boars tells the story of four wild boars – Boris, Morris, Horace and Doris

– all of which are dirty, smelly, bad tempered and rude. They could try to be

good, but they aren’t very good at

it. For example, “Horace will soak in the toilet for hours,” “Morris will…eat

all your chocolate and give you his fleas,” “Boris will break every one of your

pencils,” and “Doris will eat your very best whale, flippers and all.” Is there

such thing as a nice wild boar? Read this book and find out. Blackall’s

depiction of the hairy, bulky wild boars in ill-fitting clothing is not only

comical, but is a wonderful visual representation of Rosoff’s mock-taunting

prose. The scratchy and defined illustrations of the boars contrast with the

soft, pastel and almost paper doll like images of the girl and boy following

the boars’ shenanigans.

Rosoff, Meg. Jumpy

Jack & Googily. Illustrated by Sophie Blackall. Henry Holt and

Company. 2008. 32 pages. Ages 3-6.

Meet

two good friends - Jumpy Jack, a very nervous snail that is very afraid of

monsters and Googily, who is blue with hairy eyebrows, a long tongue and funny

trousers. The pair goes about their day with Jumpy Jack punctuating each scene

with, “There might be a monster…” and Googily checking for the monsters, as any

good friend would. As the reader progresses throughout the story, they may

notice something utterly familiar about the monster that Jumpy Jack is

describing. As any child knows, monsters can come in any sizes and that’s why

the end comes as no surprise. Blackall’s illustrations go beyond complementing

the text, but actually give hints to the reader about what Jumpy Jack’s monster

looks like. Her signature ink and watercolor illustrations truly make the text

come alive.

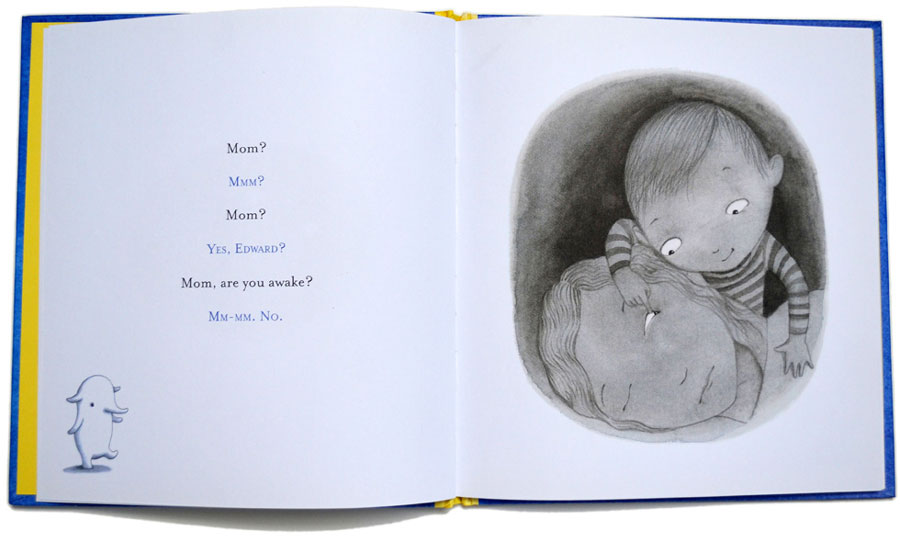

Blackall, Sophie. Are You Awake? Illustrated

by Sophie Blackall. Henry Holt and Company. 2011. 40 pages. Ages 2-5.

Edward can’t sleep. His mom, however, is fast asleep. Naturally, this doesn’t stop young Edward from asking his mother a series of questions. The conversation is familiar to any parent and child. “Why hasn’t the sun come up yet? Because the starts are still out. Why are the stars still out? Because it’s nighttime.” The illustrations are soft vignettes done in watercolor. The colors start out dark blue and gray and slowly evolve to bright yellow and orange. Coupled with the simple and familiar text, these pictures help to tell a sweet bedtime story.

An Analysis

Sophie Blackall uses Chinese ink and watercolors for all of her children’s book illustrations. To make the Chinese Ink, she grinds a special stick on a stone and wets it with water. She uses the same Schminke Watercolor set she’s had since she was little and occasionally has to replace individual colors. She starts out by reading the entire book and then reading it to her children. She then puts it away for a while and thinks about it. In an interview with Veerle Pieters. Blackall states: “When you illustrate a children’s book for instance, you have to be the architect, clothing designer, landscape artist, and town planner,” (Interview with Sophie Blackall, Retrieved on March 27, 2016). Before she even starts to work on the actual sketches, she has to decide the time period and whether the characters are animals or humans. She begins by choosing the book’s trim size. For example, Are You Awake? became a small book because she wanted it to be more intimate. She does a color character study and chooses her palette next. Then she sketches dummy illustrations of the whole book and sends them off to the editors and art directors for feedback. The painting is her favorite part.

Edward can’t sleep. His mom, however, is fast asleep. Naturally, this doesn’t stop young Edward from asking his mother a series of questions. The conversation is familiar to any parent and child. “Why hasn’t the sun come up yet? Because the starts are still out. Why are the stars still out? Because it’s nighttime.” The illustrations are soft vignettes done in watercolor. The colors start out dark blue and gray and slowly evolve to bright yellow and orange. Coupled with the simple and familiar text, these pictures help to tell a sweet bedtime story.

An Analysis

Sophie Blackall uses Chinese ink and watercolors for all of her children’s book illustrations. To make the Chinese Ink, she grinds a special stick on a stone and wets it with water. She uses the same Schminke Watercolor set she’s had since she was little and occasionally has to replace individual colors. She starts out by reading the entire book and then reading it to her children. She then puts it away for a while and thinks about it. In an interview with Veerle Pieters. Blackall states: “When you illustrate a children’s book for instance, you have to be the architect, clothing designer, landscape artist, and town planner,” (Interview with Sophie Blackall, Retrieved on March 27, 2016). Before she even starts to work on the actual sketches, she has to decide the time period and whether the characters are animals or humans. She begins by choosing the book’s trim size. For example, Are You Awake? became a small book because she wanted it to be more intimate. She does a color character study and chooses her palette next. Then she sketches dummy illustrations of the whole book and sends them off to the editors and art directors for feedback. The painting is her favorite part.

Blackall

has a very distinct style. She uses curved, thin lines and shapes that give her

pictures a soft look. The texture of her illustrations is soft and dream-like.

She uses value and chroma to her advantage in her color technique. She builds

dominance in her pictures through size, value, and contrast. Each illustration

is perfectly balanced. Her books are never just one format throughout. She uses

variation between full-page, half-page and smaller vignettes. Each book is in

harmony throughout. Blackall’s style is a bit harder to place. The best fit

would be a combination of realistic and cartoon art styles. Her illustrations

are round and soft conveying a sort of sweetness.

Though

Blackall doesn’t directly address how her background, experience and cultural

perspective influence her art, it is evident that her background in design

study at university plays heavily into her process. She doesn’t think about

each drawing individually, but instead looks at the whole picture. Her process

doesn’t only involve the illustrations, but also involves the trim size and the

end papers. She is more than an illustrator; she is a designer of children’s

books.

No comments:

Post a Comment